What are cookies, and how do they work?

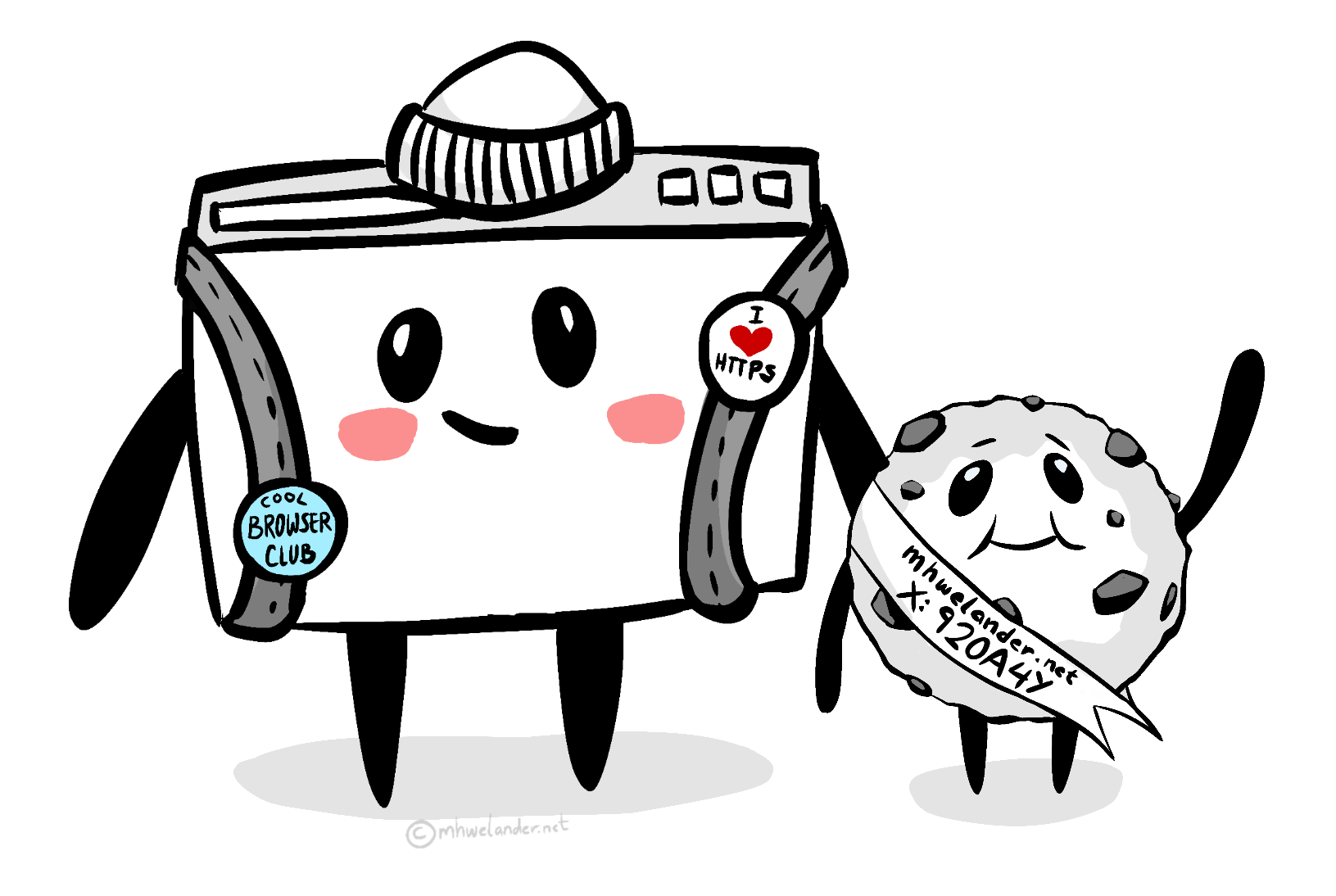

CookiesData PrivacyI’m pretty sure I know what cookies are, and how they work. But I’m also pretty sure I know what a cat looks like, and yet, drawing one without reference is.. difficult:

So when I added Google Analytics to my website, I did some research. This post is for anyone with passing knowledge of cookies who really wants to get into the crumbs.

This blog post contains some references to and thoughts about privacy legislation, but it is not legal advice.

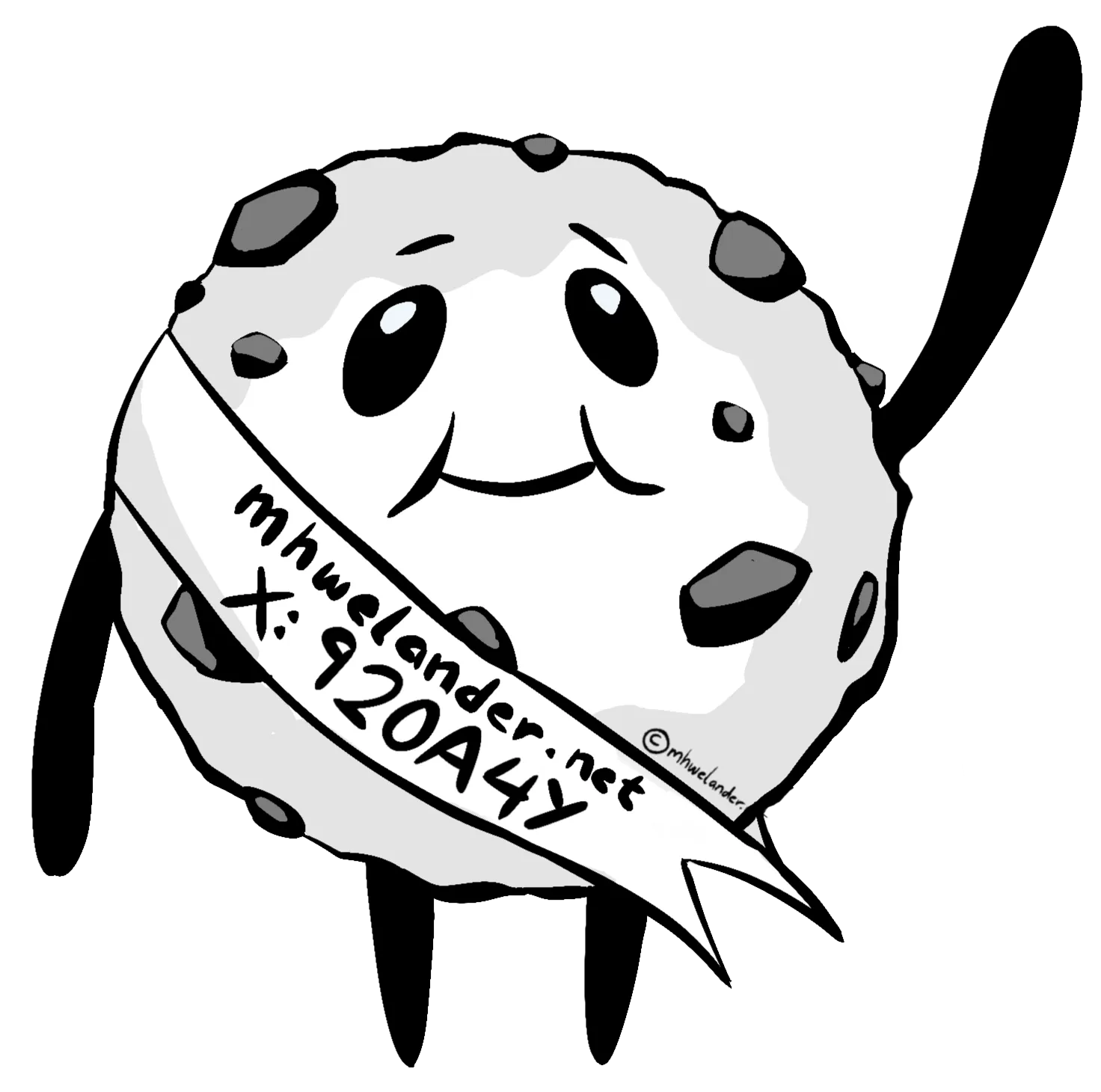

What is a cookie?

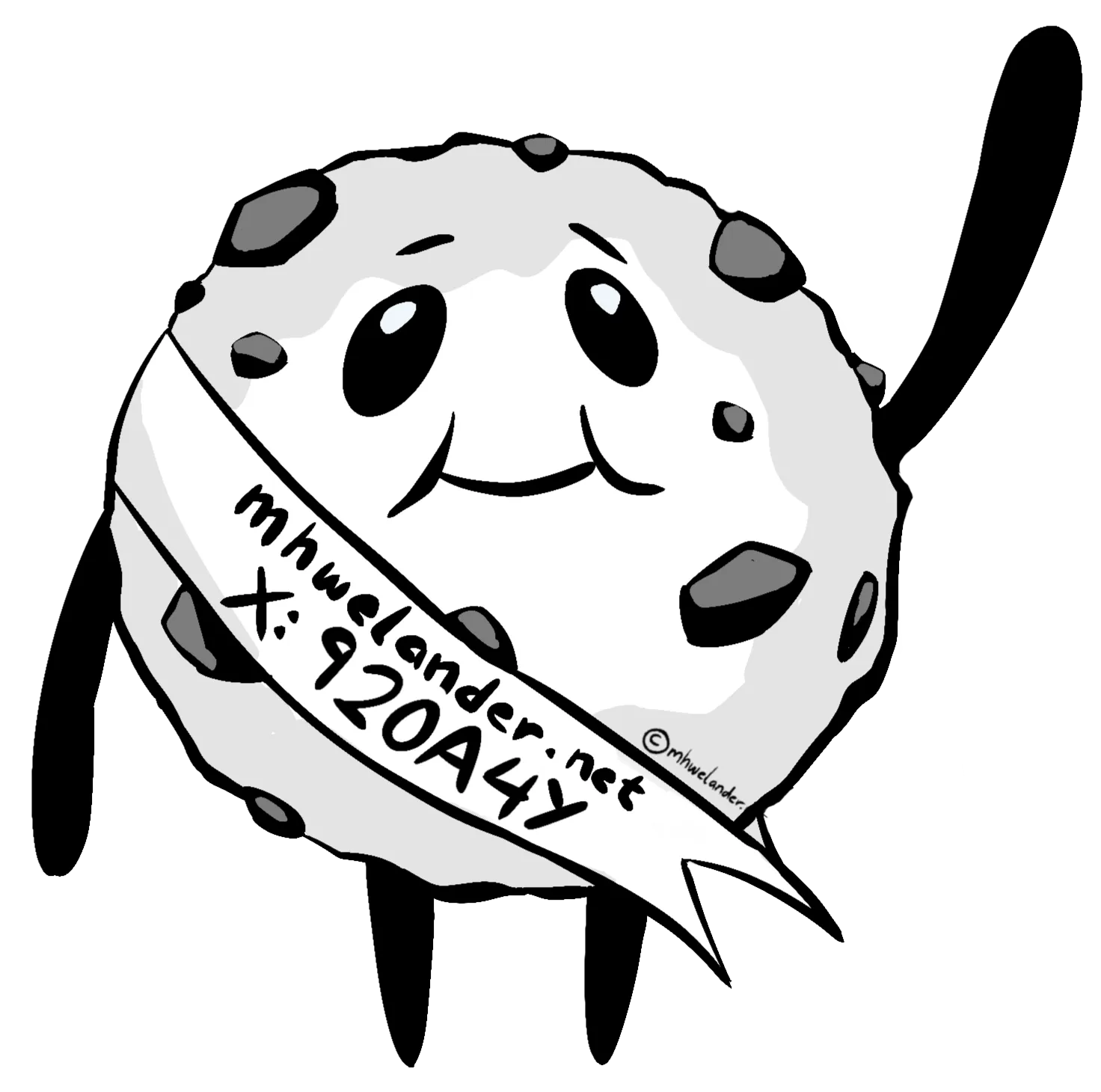

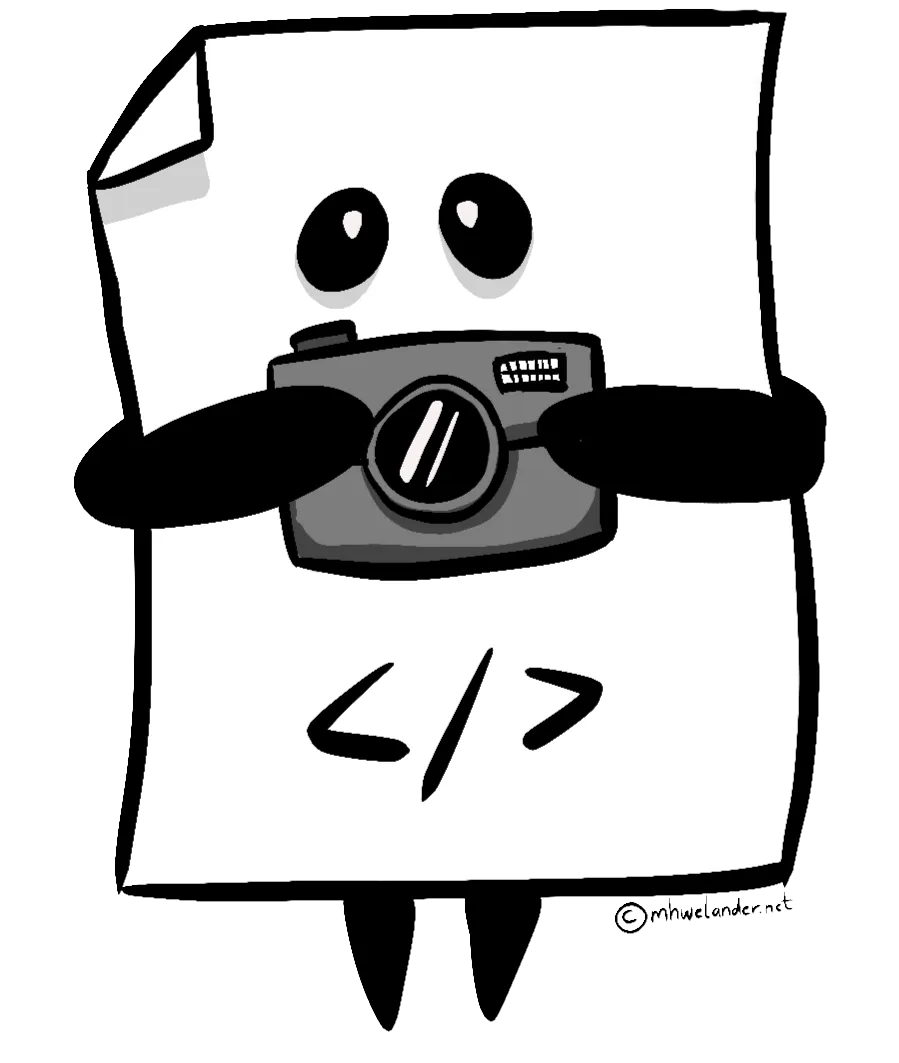

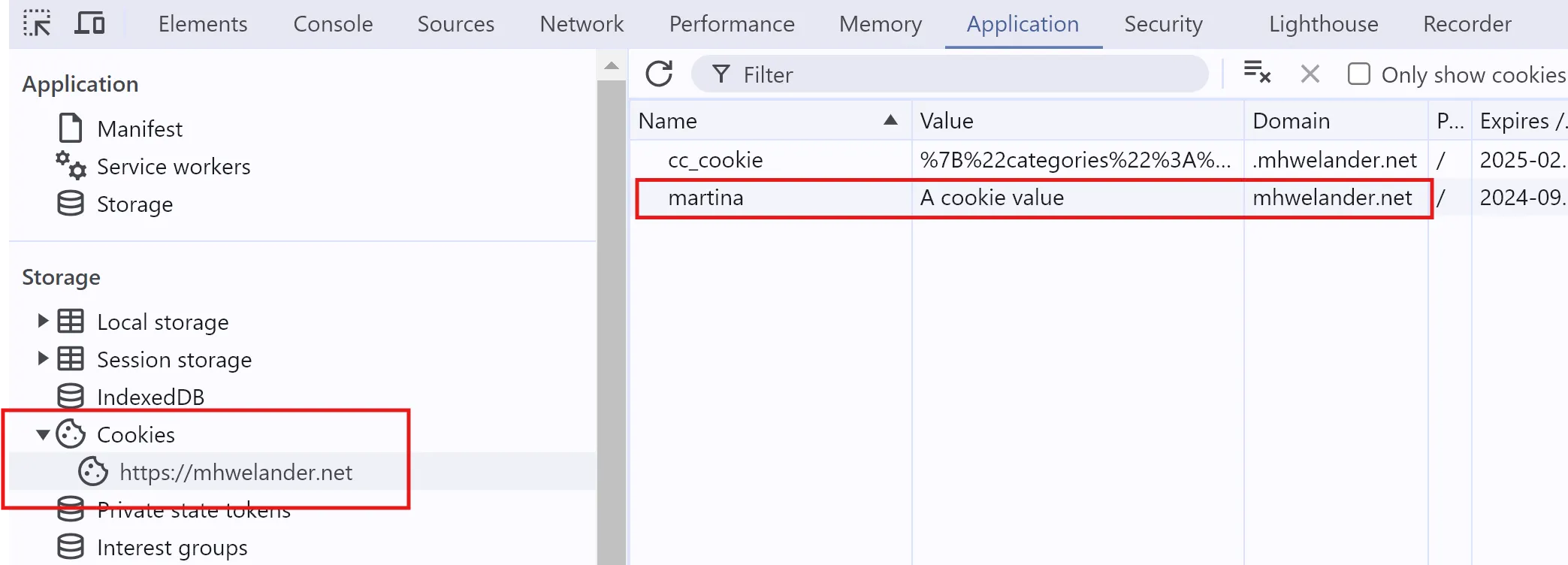

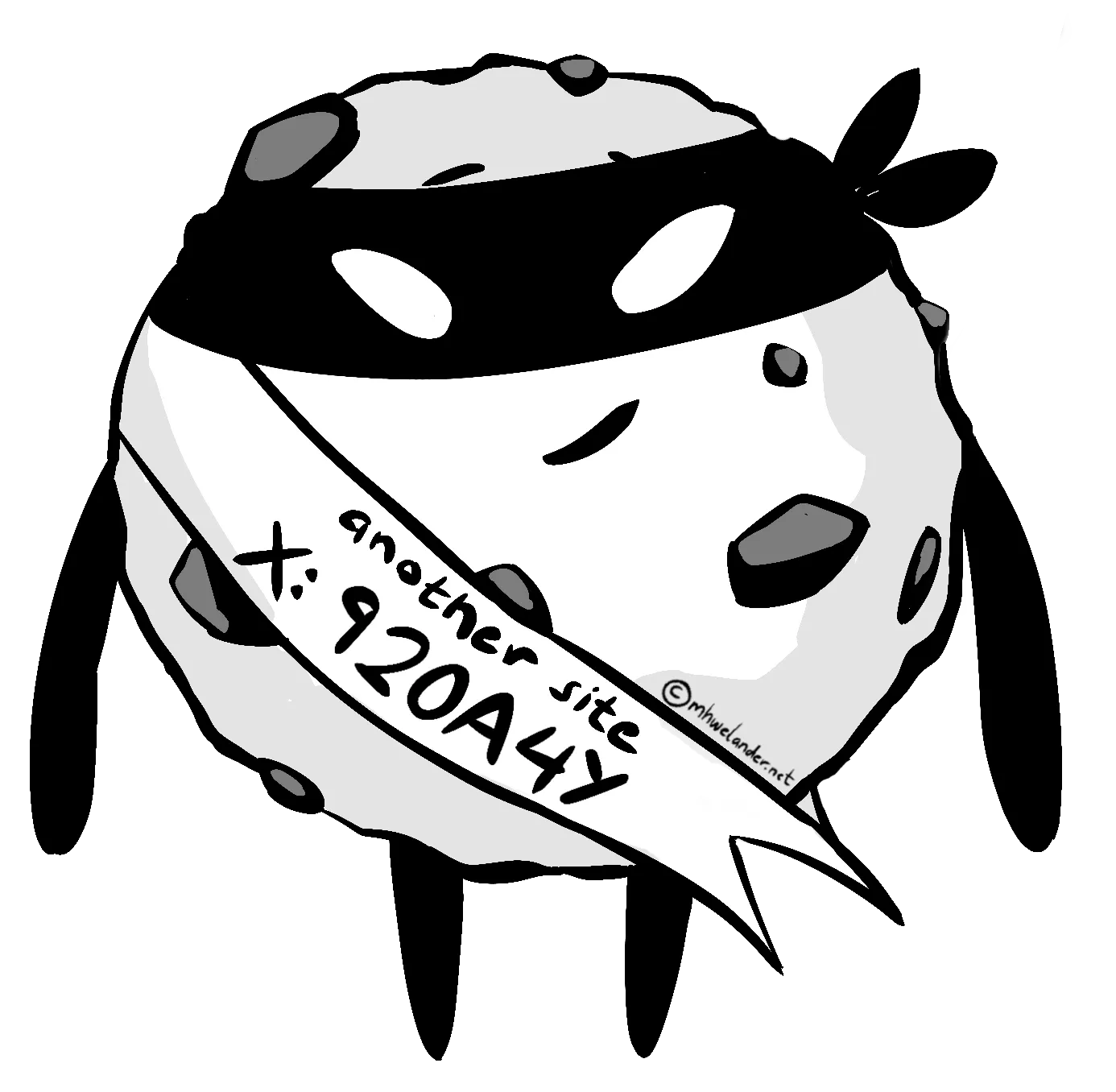

A cookie is a piece of text sent by a website to your browser that uniquely identifies you to that website. They have (at minimum) a name (X), a weird-looking value (902A4Y), and a domain (mhwelander.net):

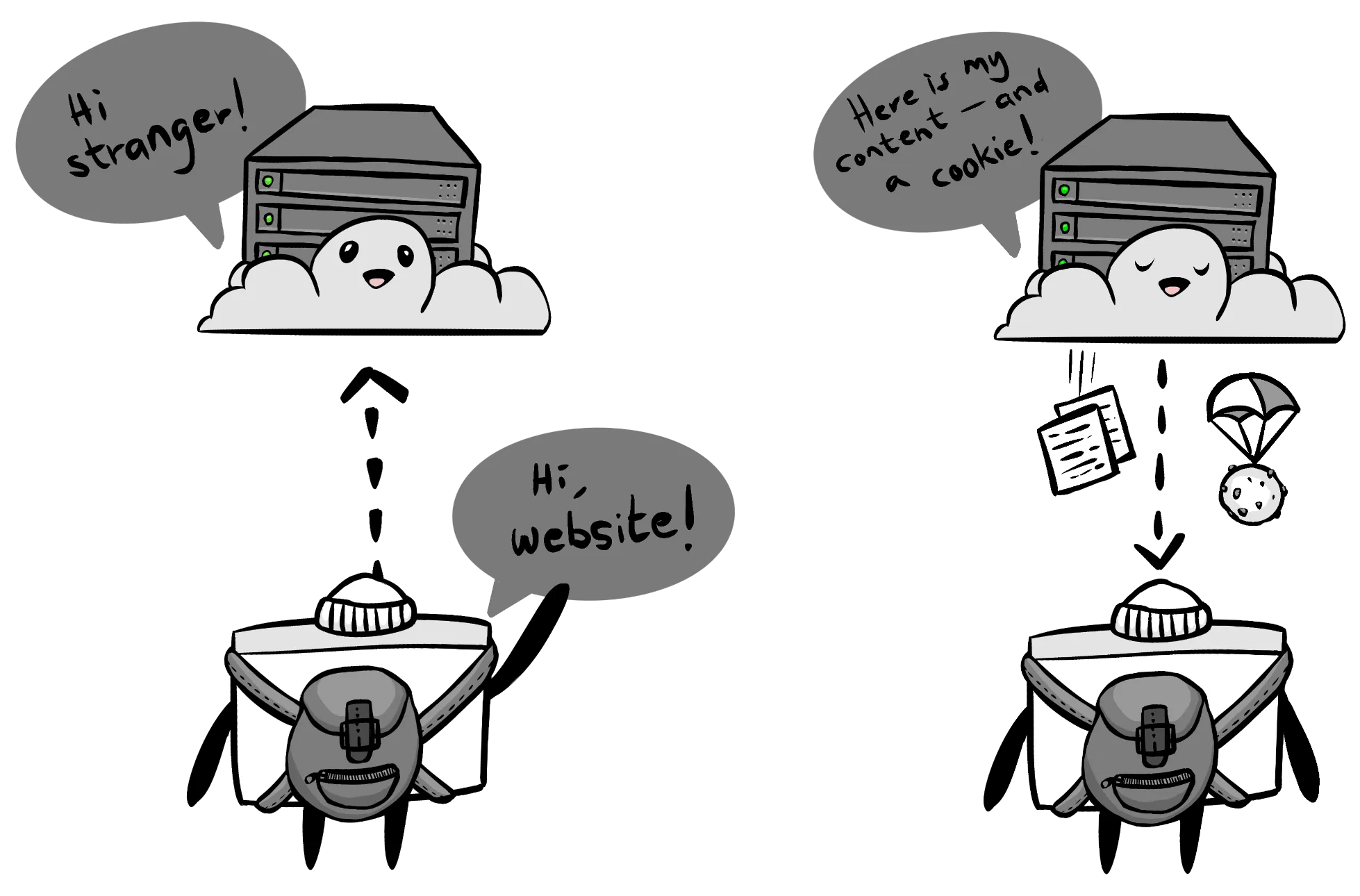

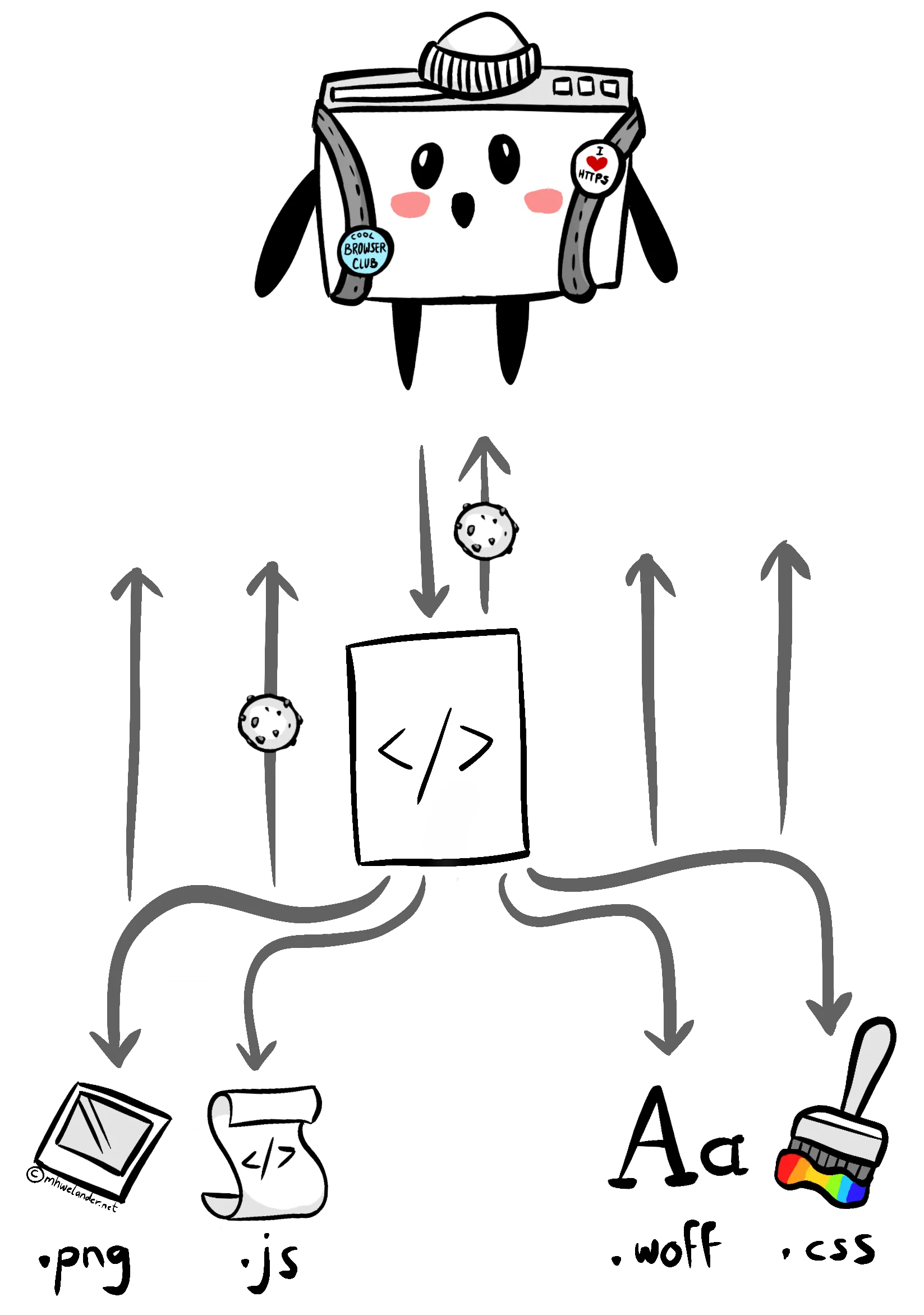

Your browser stores the cookie in a backpack of cookies, and includes it in subsequent requests to that website or that website’s resources (images, scripts) for as long as that cookie lasts:

Including relevant cookies in requests is just something that a browser does. If there’s a cookie from mhwelander.net in your backpack, your browser will include that cookie in all and any requests to mhwelander.net URLs.

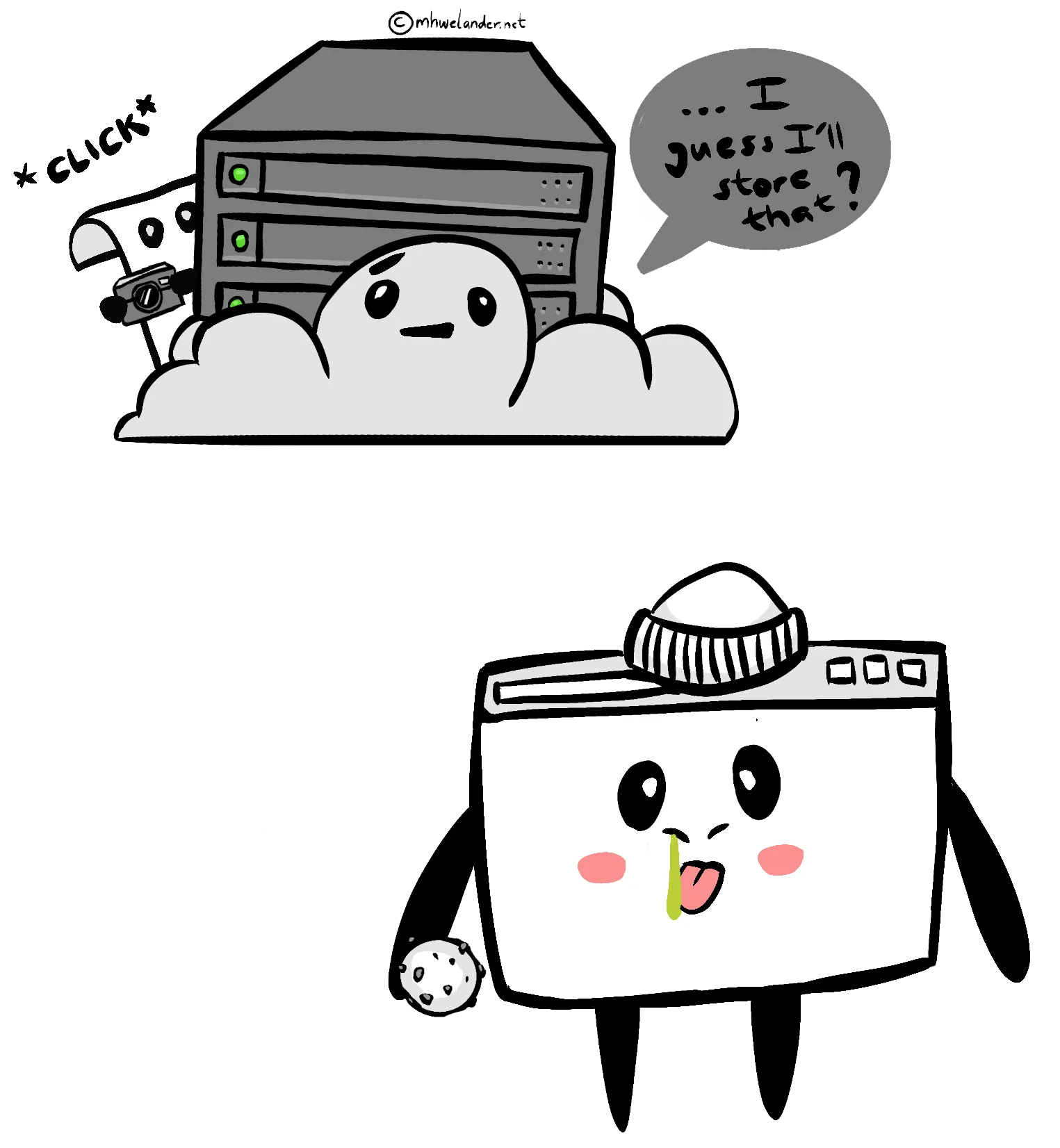

The website now has a mechanism by which to identify you between page requests and (depending on the type of cookie) between browsing sessions:

Without a cookie (or some other online identifier), a website cannot identify you between requests. You are a shiny and exciting stranger each time you request a page - like the internet of my youth old.

What is a cookie used for?

Cookies by themselves don’t really do anything; the website and the browser pass them back and forth in a not-so-thrilling game of virtual table tennis. However, once a website can identify a visitor, it can do things like keep you logged in (pretty essential) or use a script to track your activity (less essential).

I think of cookies as name tags, and there is a difference between wearing a name tag, and wearing a name tag whilst someone observes and records that you eat boogers.

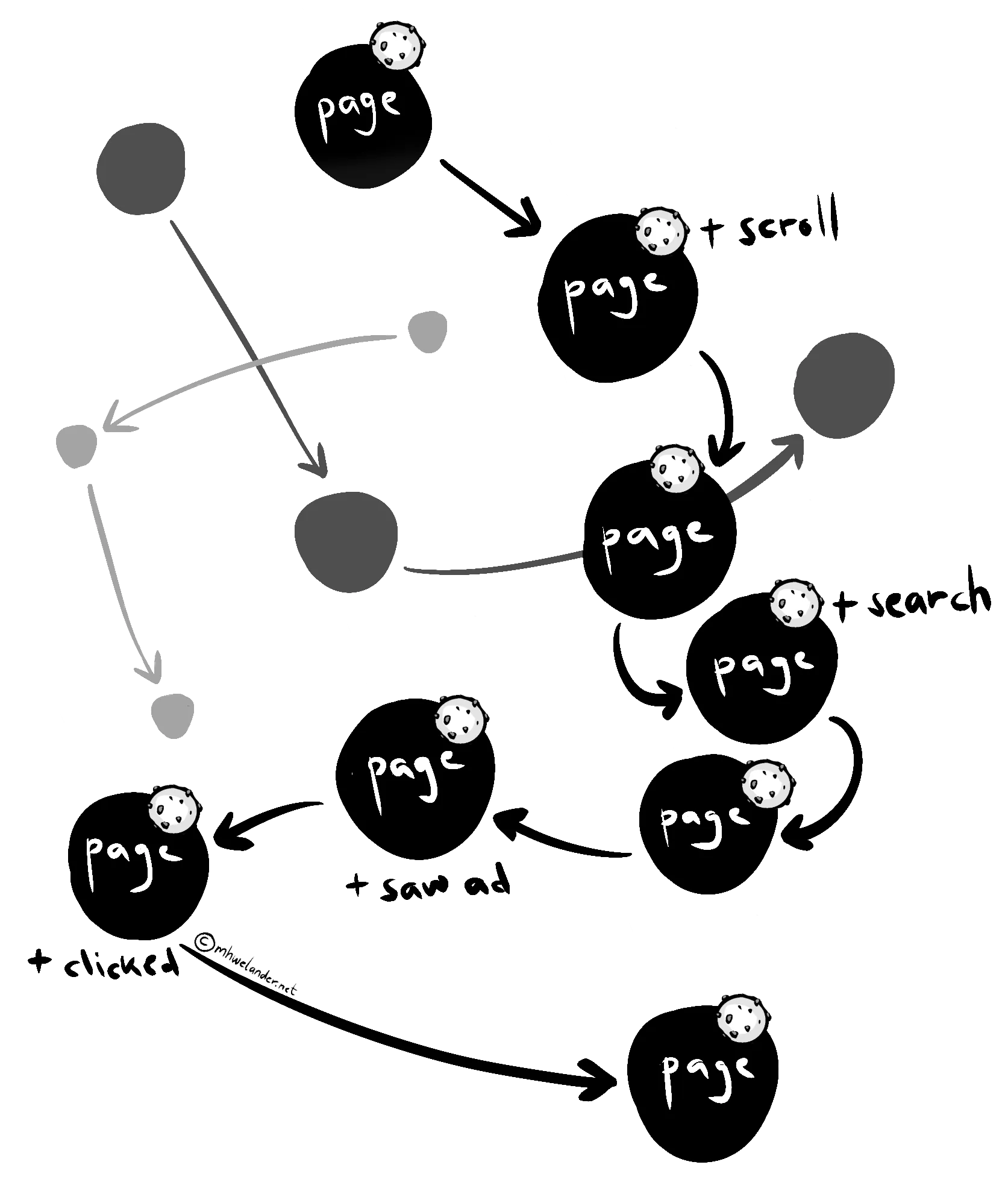

A tracking script can capture things like:

- The path you took through the website

- What you clicked and downloaded

- How long you spent on each page

- Which components you interacted with and how far you scrolled

Companies can use this data to personalize your experience and monitor trends - if you spent three sessions looking at 🐝beekeeping paraphernalia, the website might start to suggest that you buy the discounted Beginner Beekeeper Bundle.

Without a cookie, these actions are disconnected. “Someone” from Denmark looked at manual honey extractors and “someone” from Denmark for spent 10 minutes reading a single page about carpets. Is it the same person? Who knows. Is it booger lady? If you’re lucky.

But does it really matter? On this website, maybe not - if you consent, I give you a cookie and track which pages you look at on this site only. So far, not excessively creepy (you can of course still opt out of tracking - just click the preferences link in the footer).

But what if you brought that cookie with you to hundreds of thousands of websites with that same tracking script? Now it’s watching you shop, book appointments, and browse listicles about why cats suck (how dare you). This is the potential threat posed by third-party cookies with wide reach.

How long does a cookie last?

In my house? Less than three minutes.

In a browser, however, a persistent cookie lasts until you delete manually it, or until it expires. The website that issues the cookie sets the expiry date, but:

- Most browsers limit the max age (Chrome’s upper limit is 400 days) and may have additional rules that affect cookie expiry date

- Expiry dates must follow any regulation/s in the visitor’s country

By contrast, a true session cookie (a cookie issued without an expiration date) lasts until you close the browser.

Who decides which cookies a website should issue?

Technically speaking, the website owner decides which cookies a website issues to visitors - but it’s not always obvious where the cookies are coming from. Cookies can created by:

- The website itself - through server-side code or JavaScript

- An embedded resource from another website, such as a script, image, or iframe

If a cookie comes from a different website (has a different domain) than the one you are currently visiting, it is called a third party or ‘cross-site’ cookie.

Do websites really need cookies?

Some cookies are in fact essential for a website to function correctly. For example, many websites use session cookies to keep you logged. without that cookie, you can’t log in.

Cookies used for marketing purposes such as tracking and analytics are considered non-essential - they might be essential to the business, but they are not essential to the visitor.

Let’s get technical: How do cookies actually work?

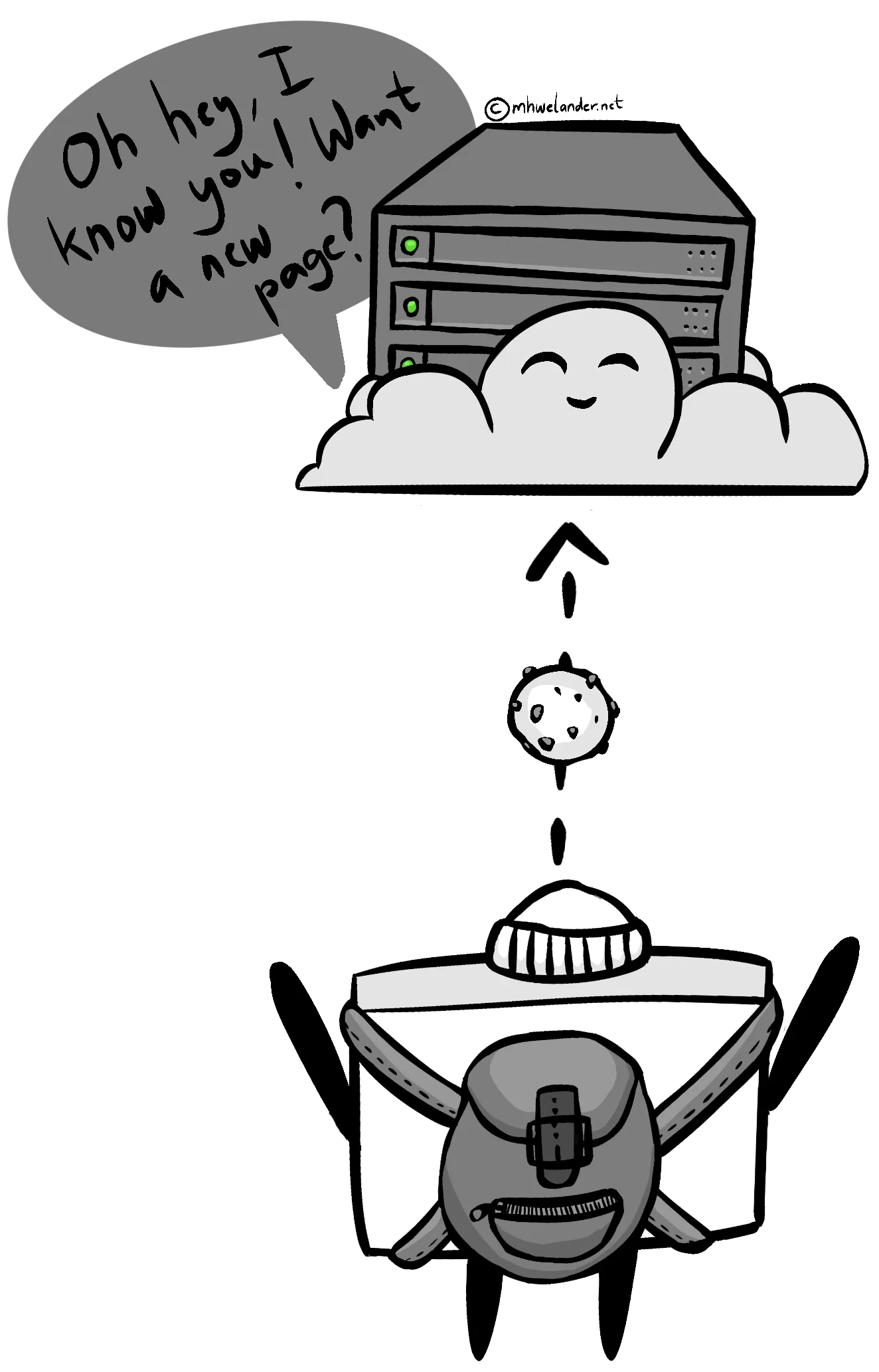

When you request a web page - let’s say, mhwelander.net - that web page sends you a response (usually some HTML). That response triggers a cascade of responses to get any referenced stylesheets, scripts, images, and fonts required. You might also receive some 🍪cookies:

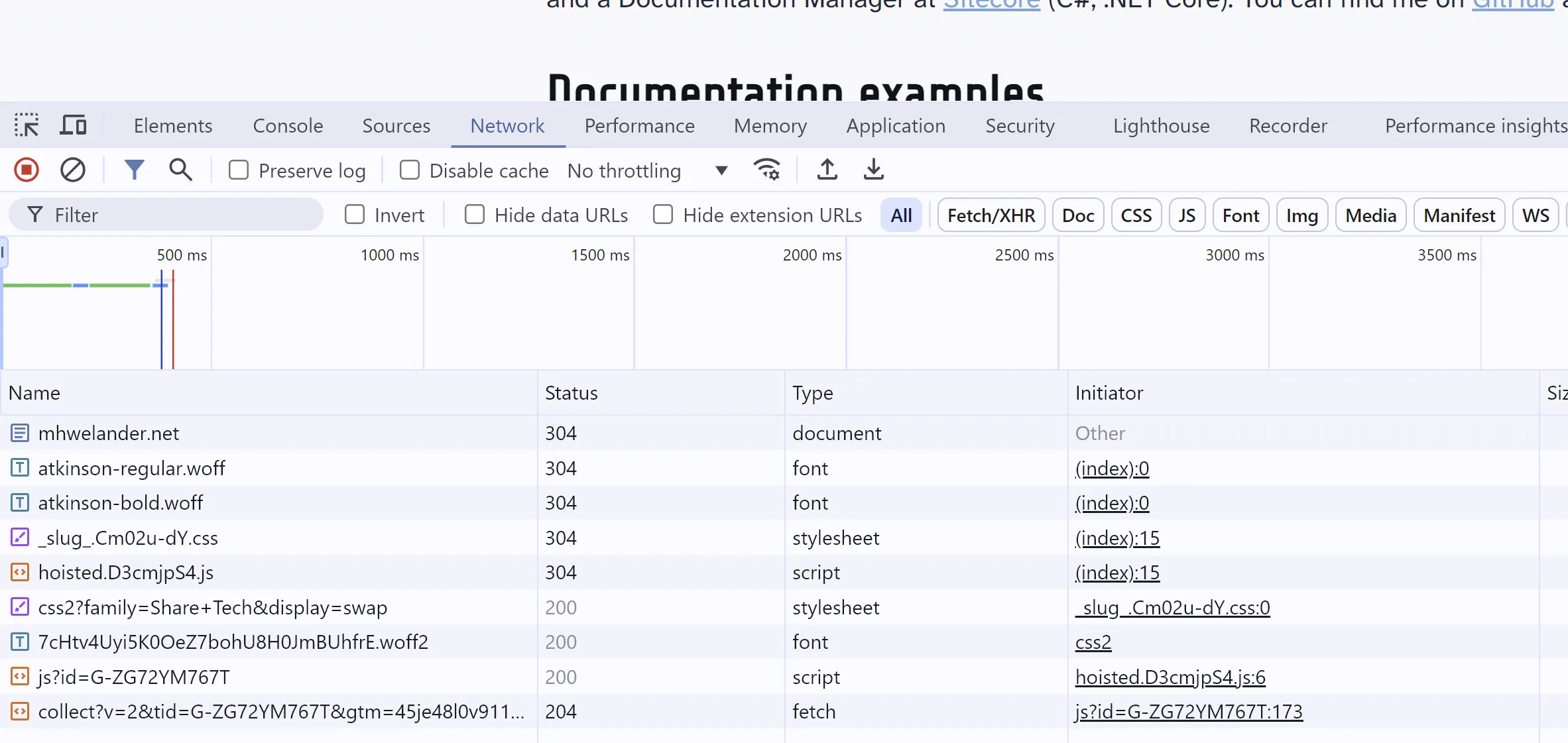

If you use Chrome, you can see the responses in Chrome Developer Tools. Click Option + ⌘ + I (Mac) or F12 (Windows), click on the Network tab, and refresh your page. Notice that the response from mhwelander.net includes various requests to get fonts, stylesheets, script files, and iframes:

I was promised cookies - where are they?

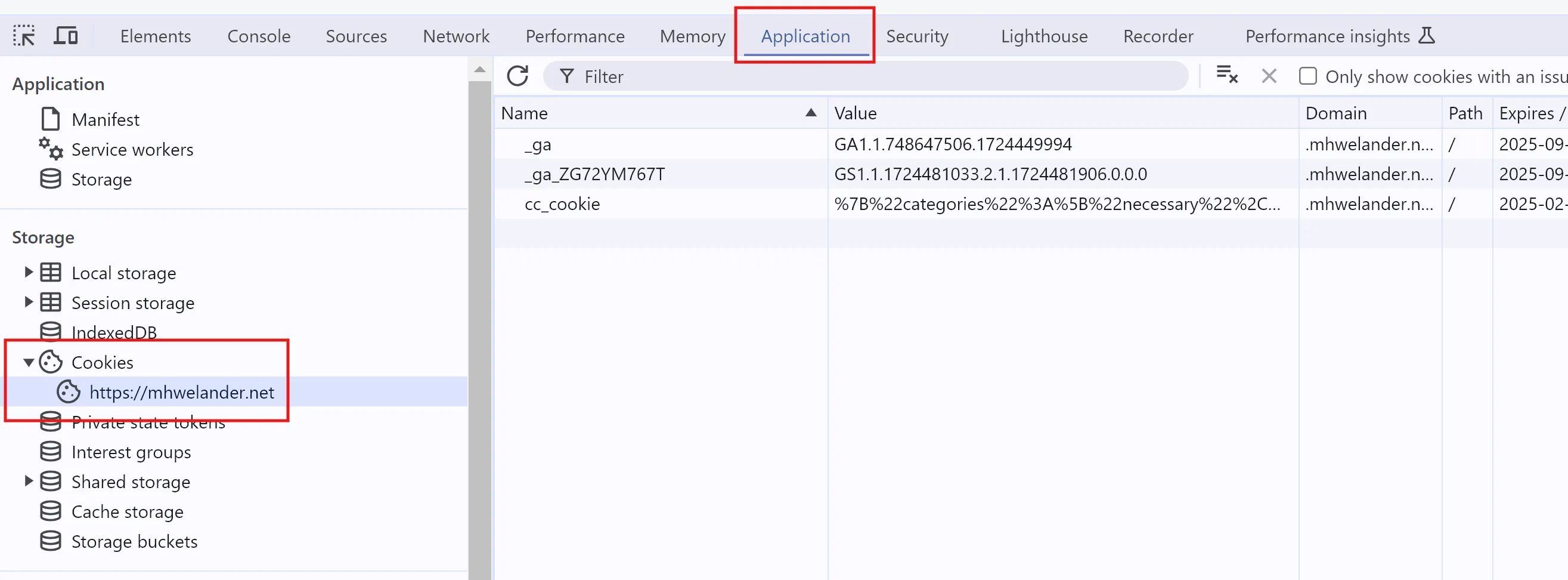

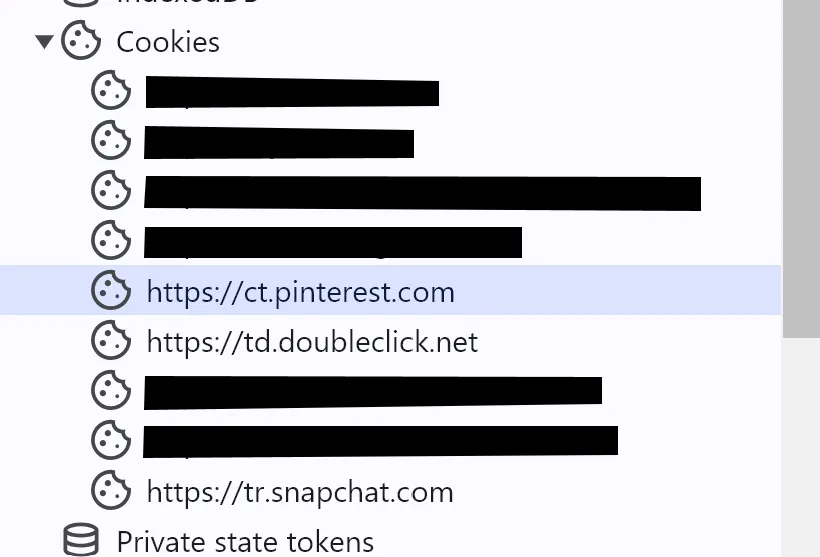

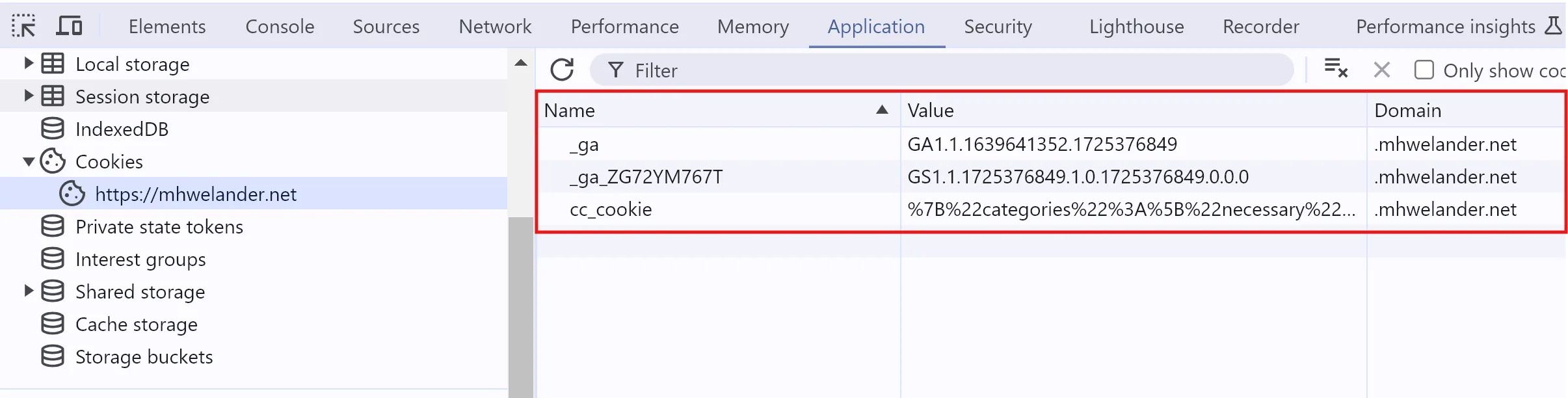

Cookies are either set by the Set-Cookie header included in one of these requests, or they are set by Javascript. You can see the cookies your browser has stored for the site you are looking at in Application tab of the Chrome Developer Tools, under Storage > Cookies > [yourwebsite]:

If a website contains iframes, cookies are organized by which ‘frame’ (including your website, which is the ‘top’ frame) is using the cookie in a request or a response:

An iframe is a reference to a third-party resource - just like an image or a script - and can set cookies if the parent frame allows it.

Setting cookies

Cookies can come from two places:

A response header can do certain things that Javascript cannot - such as creating a third-party cookie, or marking a cookie as HttpOnly. Javascript code also cannot access cookies from another domain than the one you are currently on.

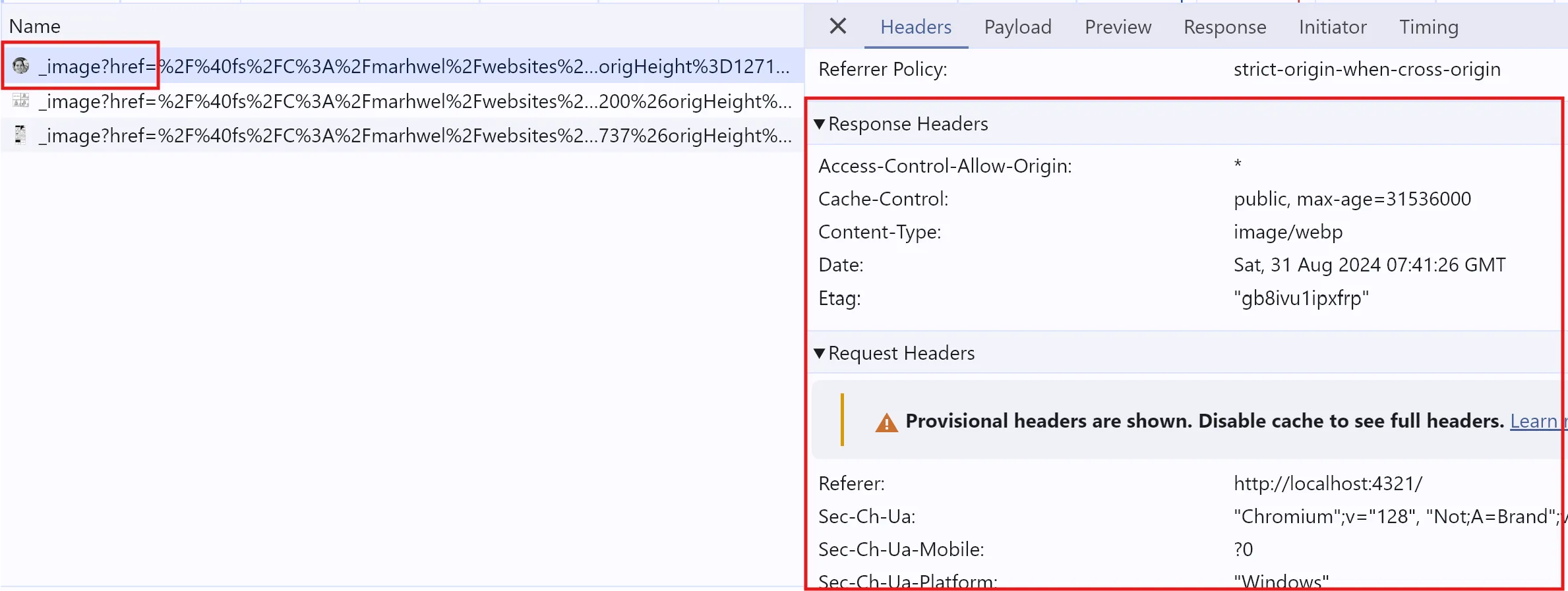

Setting cookies with a HTTP response header

All requests and responses includes headers. Headers are meta data about the request - for example, the Content-Type header describes kind of content that was requested. The following request returns an image/webp:

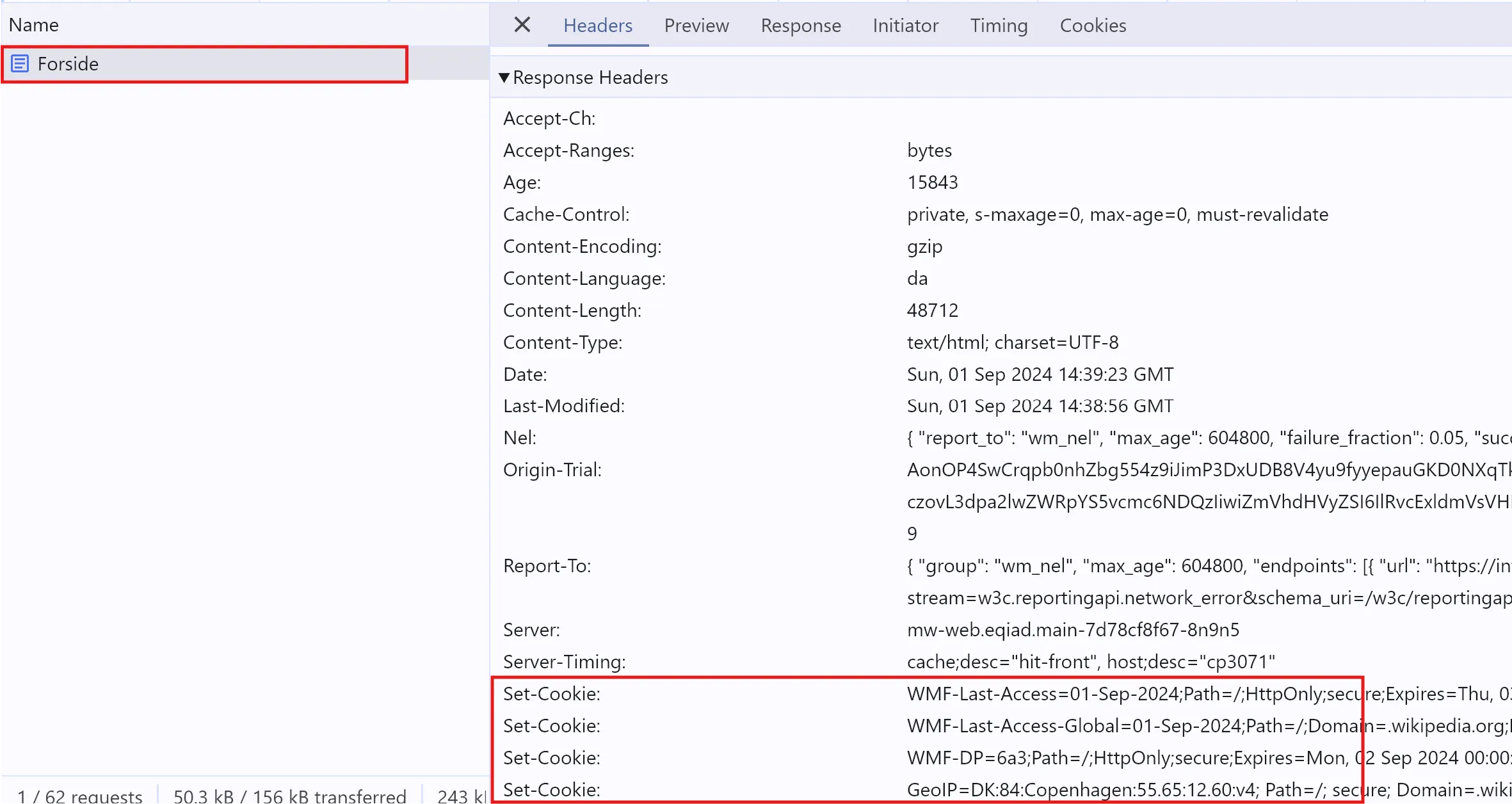

A response can also set a cookie via the Set-Cookie header. You can set a cookie with a response from a document, or a script, or even an image. When I load the Wikipedia homepage, Forside document sets several cookies:

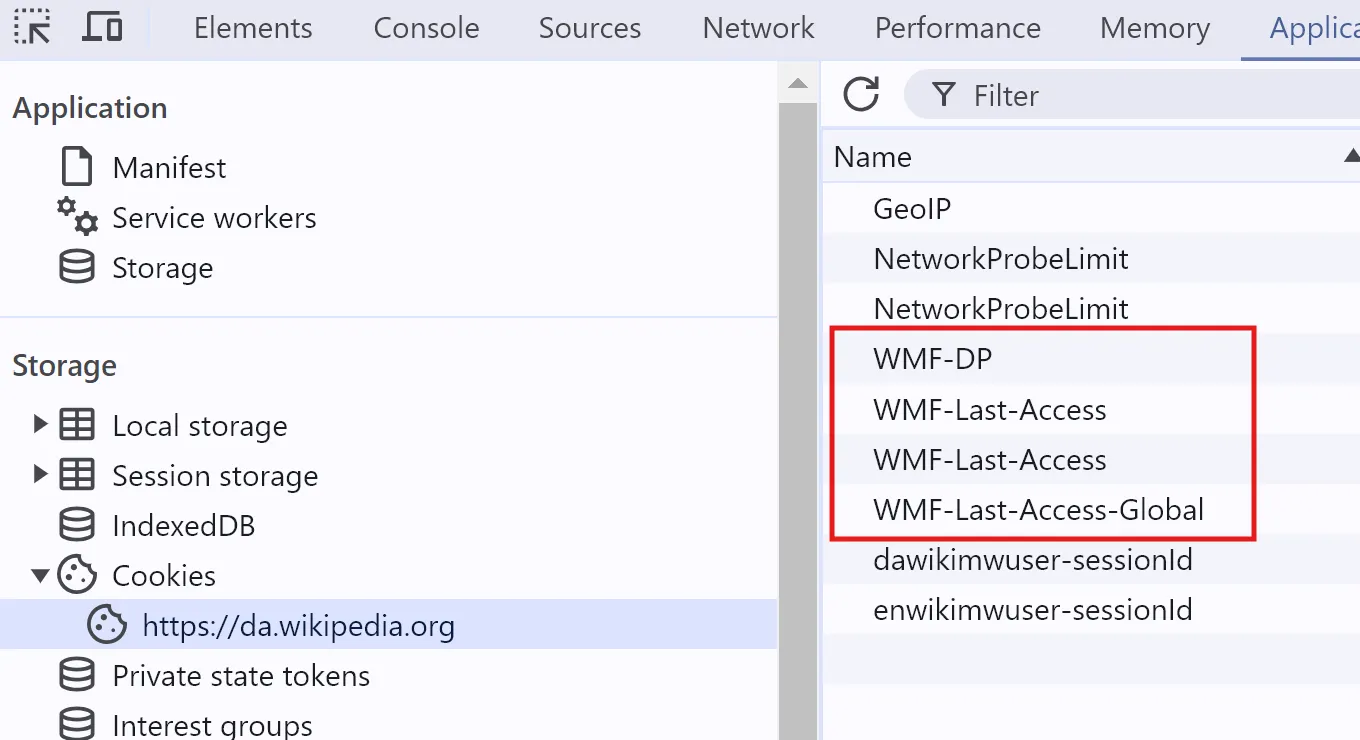

These cookies show up under Application > Cookies:

In this particular example, all cookies are first-party - they come from wikipedia.com. However, the Set-Cookie header can also be used to set a third-party cookie.

Setting cookies with Javascript

Javascript can also set cookies - this example sets a cookie named martina that expires in 2030 (in reality, browsers have a max age for cookies):

document.cookie = "martina=a cookie value;expires=Thu, 18 Dec 2030 12:00:00 UTC"

You can paste this one line into the Console tab and press enter to create a genuine cookie - it will appear alongside other cookies in the Applications tab:

Any script can create a cookie. That includes scripts hosted on your own domain and scripts from other domains, like Google Tag Manager:

<script async src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=G-12345667"></script>

However, scripts can only create cookies for the current domain - in other words, they can only create first-party cookies. If you attempt to run the following in the Console tab on mhwelander.net, the cookie will not be set - the domain does not match the website you are on:

document.cookie = "martina=a cookie value;expires=Thu, 18 Dec 2030 12:00:00 UTC;domain=notmhwelander.net"

Even the Google Analytics script creates a first-party cookie - the domain is mhwelander.net:

HTTPOnly cookies

Cookies set by the Set-Cookies response header can be set to HttpOnly. This means that a cookie can only be accessed by the server (included in the Cookies request header), not by Javascript. Requests initiated by Javascript will still include this cookie, but the script itself cannot access it.

Accessing cookies

You can access a cookie through Javascript via the window.cookie property if:

- The cookie is from your domain

- The cookie is not marked as HttpOnly

If a cookie is from another domain, it will be included in Cookies header of any requests going back to that domain - that’s it. For example, if a cookies’s domain is *.tiktok.com, the browser includes it in any requests to *.tiktok.com.

But this is how many tracking script work - they track what you do on site A and send a request back home to Site B with your cookie in the Cookies request header, like a stamp on an envelope.

| Current domain | HttpOnly | Access |

|---|---|---|

mhwelander.net | ✓ | * Accessible while on mhwelander.net (server-side code)* Included in requests to mhwelander.net via Cookies request header |

tiktok.com | ✓ | * Accessible while on tiktok.com (server-side code)* Included in requests to tiktok.com via Cookies request header |

tiktok.com | * Accessible while on tiktok.com (Javascript or server-side code)* Included in requests to tiktok.com via Cookies request header | |

mhwelander.net | * Accessible while on |

Third-party cookies

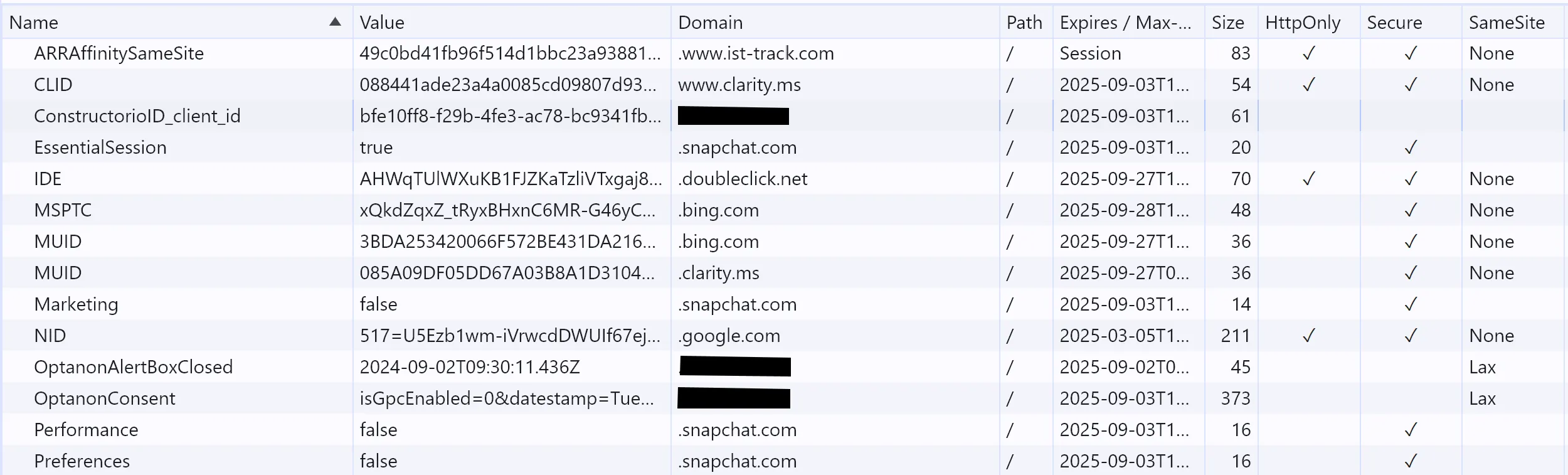

On many websites, particularly after you accept non-essential cookies, you will suddenly see cookies from a list of other domains - often domains you do not recognize or have never visited. These are third party or ‘cross-site’ cookies.

The thing that makes them third-party cookies is this: the cookie domain does not match the current site. That’s it. If you include a mhwelander.net resource on your website that sets a cookie, the domain of that cookie is mhwelander.net and it is a third-party cookie in the context of your website.

I visited ███████.com, accepted all cookies, and looked in the Application tab - notice that most of the cookies are from other domains and are therefore third-party:

It is the context in which a cookie appears that makes it third-party or first-party; the cookie itself is not inherently third or first party.

Where do they come from and how are they used?

When a website owner embeds a resource from another website, such as an image or a script, the response from that resource can include a Set-Cookie header. This sets a third-party cookie - it comes from a website you might never have visited.

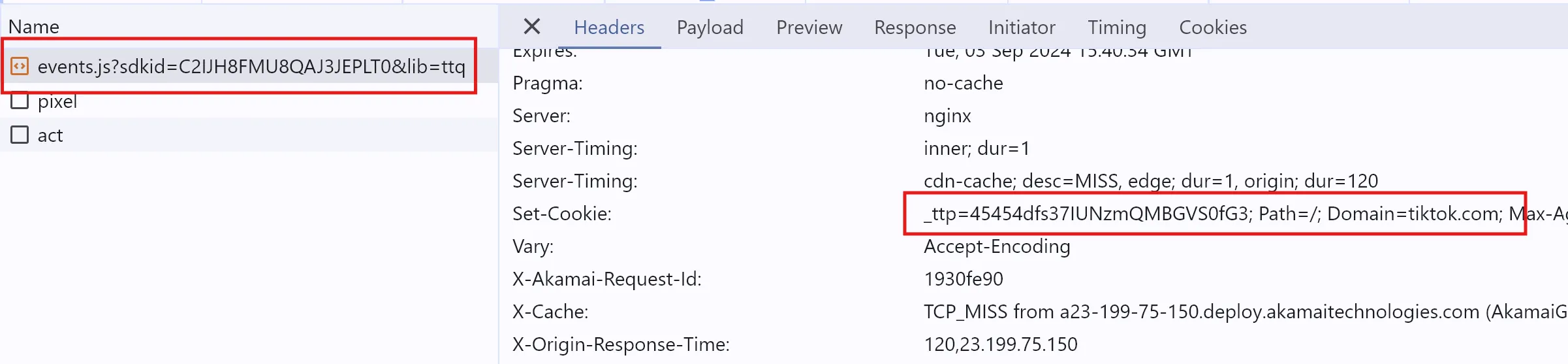

For example, the HttpOnly _ttp cookie (TikTok) is set by the Set-Cookie header when you load events.js script from analytics.tiktok.com (the cookie is set by the request, not the Javascript itself).

Set-Cookie headerThe tracking script is able to send information about your activities back home to the Planet TikTok because the request to *.tiktok.com/events.js automatically includes your *.tiktok.com cookie in the Cookies request header.

Here’s the critical part:

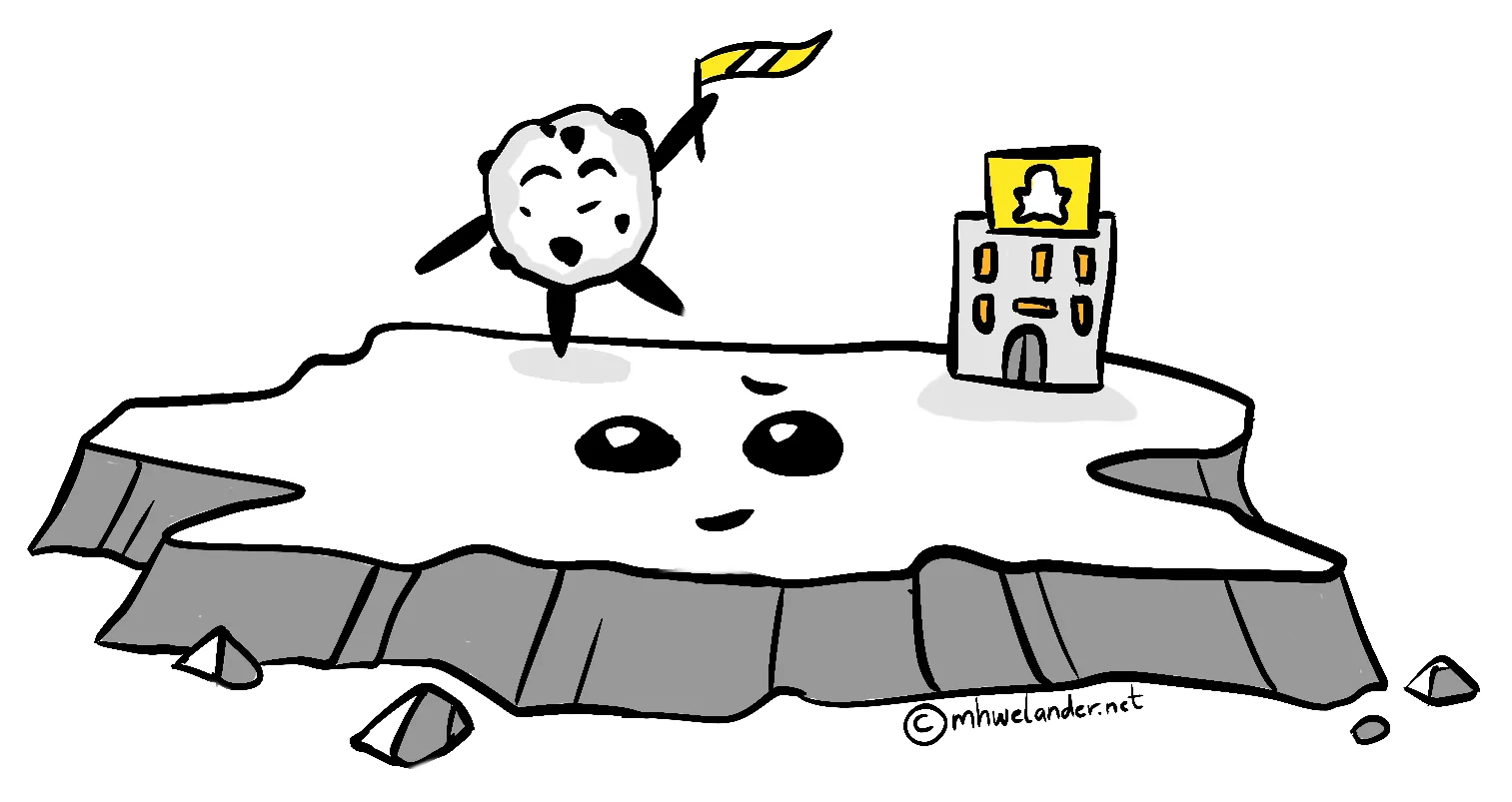

any other website you visit with the TikTok tracking script is able to send your TikTok cookie back to TikTok in this way

This means that you can be tracked as a single individual across the hundreds of thousands of websites that implement this script. TikTok isn’t exactly an obscure advertising platform - and neither is Google, or Amazon.

And remember - we invite these cookies by adding tracking scripts to our websites. We invite them, and we give them a way to phone home and gossip about us (sometimes too much, if we misconfigure the script):

And frankly, for advertising purposes - third-party cookies are useful! By collecting data about an individual across many, many websites, advertising platforms are able to target ads with incredible accuracy. This is great for anyone who uses the platform to advertise - and great for the platform, because we pay them.

And, if I’m being honest, I’m not too mad about it when Instagram shows me an ad for exactly the thing I want. I was looking for moisture-wicking socks with a reinforced heel - how did you know?

But it’s a bit creepy. In fact, under the right (or wrong) circumstances, it can be outright damaging.

What’s the big deal?

If you steal my laptop and look at my cookies, you probably (PROBABLY!) won’t get a lot of interesting information out of them in isolation.

But a cookie, particularly a third-party (cross-site) cookie that really ‘gets around’, can compromise your privacy online. Let’s say you have lived a wild, third-party cookie-accepting life online up until this point.

Many tracking services and advertising platforms have stored a lot of data about your online activities - and it’s all linked together by a single identifier.

And here’s the thing about all of this data:

- You don’t know exactly what data has been collected

- People mess up, and data breaches happen

For example, a misconfigured script on 💅 Mr. Bob’s Nail Salon’s booking form might have sent your name and email address to an ad platform - it probably violates the terms of said platform, but Mr. Bob slapped the tracking script on his site over a boozy lunch in 2013 and hasn’t thought about it since.

In isolation, this might not seem like it matters. However, it probably does matter if the same tracking script, using the same cookie, later ⚠️records you downloading the patient handbook for a specific disease from a hospital website.

In this example, specifically because the cookie’s cross-site presence, a single identifier now links your name and email address to your expensive nail habit.. and ⚠️ your private medical information - and all of it has been sent to a third party. This may sound like a worst case scenario, but it seems to happen all the time.

First-party still make it possible to track your activity across sessions on a single website - this could absolutely be a problem if a hospital accidentally sends some of your patient data to a tracking service. The risk increases with a cookie that stalks you all over the internet.

Oh no! What’s being done about the cookies?

Data privacy isn’t a new thing, but I started to have more conversations about cookies and tracking in particular in the mid-2010s - there’s a great timeline of data privacy online over here. Suffice to say, in 2024, a large percentage of people understand that their online activities leave prints.

There is a lot of privacy legislation that affect cookies, and your browser is getting protective by default (which I didn’t know until recently).

Privacy legislation

The ✨general vibe✨ of privacy legislation centers on active consent and the right to be informed (in the European Union - and many other countries and/or states have GDPR-like legislation.)

The EU ePrivacy Directive has been around since 2002 and mentions requiring consent to store information (such as cookies) on user equipment. GDPR has applied in the European Union since 2018, and requires consent (with some caveats) to process personal data - which includes online identifiers.

I actually started writing this blog post because I wanted to understand exactly why Google Analytics requires consent, and here it is: it issues a cookie (ePrivacy Directive), and that’s an online identifier that is being processed and stored by Google (GDPR).

Browsers

Browsers themselves are getting generally more protective of their meat-flavored pilots (that’s you and me). Where third-party cookies are concerned, the default behavior of several browsers is to block them, which means you have to actively opt in to receive these cookies.

Firefox has done many other things to keep users safe on the internet, including blocking third-party cookies by default. There’s a beautifully illustrated timeline here. Safari similarly blocks third-party cookies by default.

Chrome is.. working on it, kind of. You CAN block third-party cookies, but they are not blocked by default. But Chrome is owned by Google, who might just be making a little bit of money from online advertising. :)

You can also choose a privacy-focused browser like Brave.

No cookies, no problems?

No, not really. There are many other ways to fingerprint a person, even across browsers (seriously, check out that website). There’s a reason why GDPR vaguely refers to online identifiers.

Third-party cookies seem like they might be doomed, and unnecessary/non-essential first-party cookies still require consent - something that often causes a dramatic drop-off in recorded website traffic. Naturally, a lot of companies are asking:

How can I track someone’s activity ‘anonymously’ - in a way that does not require active consent?

Cookie-less tracking offers an alternative - but you can’t track visitors between websites, or even between sessions. As soon as your tracker uses an identifier that persists or can be reliably re-created across sessions, I would argue that it’s processing personal data, and personal data requires consent.

For example (opinion ahead) - if you fingerprint someone by generating and storing a hash of their IP address, user agent, and some other browser information that makes that hash more reliably unique, without using a sprinkle of some kind of time-limited salt.. that’s starting to smell like a cookie in a Halloween costume to me.

Most cookie-less trackers that I have looked at do use some kind of time-limited salt. I still have Some Thoughts™️ about consent there, but that feels like an entirely separate blog post, and a whole new cast of characters.